Superscript

STEAM For Babies & Tots

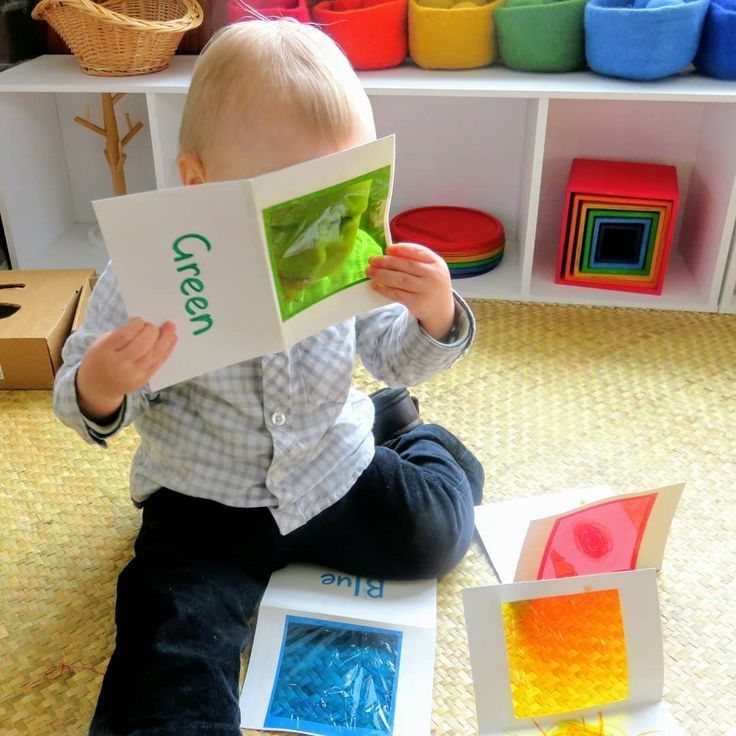

To teach science to babies, focus on hands-on exploration and everyday experiences that encourage curiosity, such as feeling different textures, exploring natural objects like leaves and rocks, and observing cause and effect through simple activities like watching bubbles. Ask open-ended questions to foster scientific thinking, provide simple discovery tools like buckets, and read books about familiar objects and nature to build their vocabulary and understanding of the world around them.

Engage Through Play and Sensory Experiences

Explore textures: Give babies safe objects of different shapes, sizes, and textures (leaves, shells, soft fabric) to touch and feel, prompting them to notice similarities and differences.

Play with bubbles: A bubble machine or wand is a great way to encourage hand-eye coordination as babies reach for and try to grab bubbles.

Explore sounds: Let babies feel the vibrations from music by being close to speakers, or feel the vibrations of their parent's voice when snuggling.

Use simple tools: Provide infants and toddlers with tools like small pails, buckets, and safe magnifying glasses to encourage discovery.

This video demonstrates how babies explore science concepts like bubbles and textures:

Foster Curiosity with Language and Questions

Describe experiences:Use language to help babies make sense of their world by describing what they see, do, and feel.

Ask open-ended questions:Even if they don't answer, asking "What do you think will happen?" or "I wonder why?" can help develop their scientific thinking skills.

Wonder together:Observe how babies create their own questions and problems as they play and wonder with them.

Value their questions:Encourage their natural curiosity by valuing their questions and finding answers together.

Incorporate Science into Everyday Life

Nature walks: Take babies on walks to explore nature, and consider using tools like kid binoculars to spot wildlife.

Reading books: Read books with babies that feature nature, people, and familiar objects to expand their vocabulary and understanding.

Building and blocks: Activities like building with blocks help children learn about problem-solving and cause and effect.

This video explains how to incorporate STEM activities with children:

Create a Supportive Environment

Allow time and space for exploration: Give children the freedom to engage in hands-on activities and experimentation.

Embrace messiness: Recognize that science explorations can be messy, and create a safe space for practice and experimentation.

Support further exploration: After an activity, encourage children to ask new questions or try variations to deepen their understanding.

Baby Science & STEAM

STEAM, which stands for Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Math, is a way for infants and toddlers to develop lifelong learning skills. STEAM experiences can help children develop:

Creativity: STEAM encourages children to think outside the box and use their imaginations.

Communication: STEAM helps children develop communication skills.

Problem solving: STEAM helps children develop problem solving skills.

Mental flexibility: STEAM helps children develop mental flexibility.

Wonder: STEAM helps children develop wonder.

Persistence: STEAM helps children develop persistence.

Here are some tips for introducing

STEAM to infants and toddlers:

Support their natural curiosity: Infants and toddlers are naturally curious, and STEAM can help support that curiosity.

Encourage creative thinking: Encourage children to use their imaginations and think creatively.

Help them make connections: STEAM can help children see how abstract concepts apply to the real world.

Provide a supportive environment: A child's developmental abilities, interests, and relationship with their caregiver can all impact their STEAM learning.

You can also check out STEAM Concepts for Infants and Toddlers, a book that provides illustrated vignettes to help caregivers learn how to use STEAM concepts with infants and toddlers.

Infant and Toddler STEAM: Supporting Interdisciplinary ...

For infants and toddlers, the exploration of STEAM is part of the development of lifelong learning skills in cognitive development...

Building The Foundation for STEAM

in Infants and Toddler

It’s Never Too Soon to Start

In recent years, there here has been great focus on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) across the US. Meanwhile, Apple Montessori has incorporated STEAM into our curriculum for decades. Why the extra A in STEAM? It stands for Art for a more well-rounded education (more on that later).

We believe it’s important to get children started on STEAM even before they enter elementary school, and in fact, the educational activities they take part in during the infant and toddler years can build a strong foundation for the STEAM subjects they’ll study later on.

Young minds are natural sponges, able to absorb the foundational concepts of STEAM at a young age, then apply them to many aspects of their lives in the classroom and beyond.

What infants and toddlers do when they’re learning might not look like it has a lot of connection to the homework they’ll be doing once they hit middle school, but early exposure to STEAM education helps later learning in three ways:

Helps children become familiar and comfortable with basic, foundational concepts like counting, dividing, and sorting.

Builds a toolkit of essential learning skills like communication, critical thinking, and creativity.

Shows students that there is a practical, concrete application to abstract concepts like subtraction, division, and momentum.

Experimenting with hot and cold

Infants and toddlers are also incredibly receptive to learning these skills and subjects. They are incredibly active learners who love to explore, investigate, and discover. As a Montessori program, we give our students the opportunity to be active, engaged, and take charge of their own learning. By encouraging these natural tendencies, we can open up the fascinating and wonderful world of STEAM to them right from the beginning.

“…STEAM and Montessori are highly complementary, with their emphasis on the child determining what he learns through hands-on experimentation.” (Three Minute Montessori)

Why the A?

Lately, educators have changed their focus from STEM to STEAM.

The addition of the “A” for Art recognizes the importance of creativity and out-of-the-box thinking in a well-rounded education, not as a separate realm but as a key pillar.

Art not only helps young children express themselves, it also helps them analyze and problem-solve. As Parents puts it, “By counting pieces and colors, they learn the basics of math. When children experiment with materials, they dabble in science. Most important perhaps, when kids feel good while they are creating, art helps boost self-confidence. And children who feel able to experiment and to make mistakes feel free to invent new ways of thinking.” Down the road, design and creativity can play a crucial role in setting up rigorous scientific experiments or creating digital apps and platforms.

How We Build a Foundation for STEAM

Many parents wonder how we can set the foundation for learning these difficult and abstract concepts at such an early stage.

We certainly don’t spend a lot of time teaching our infant and toddler students long division or the Pythagorean theorem. Instead, we meet them at their level and provide them with multisensory, hands-on experiences that are designed to introduce them to STEAM topics in a way that engages their senses, keeps their hands busy, and fascinates them.

Here are some of the ways we introduce each STEAM subject to our students.

Science

Learning to love science begins with exploring the natural world, and this kind of curiosity is something infants and toddlers are already experts in. By guiding their curiosity, we help them learn about the way the world around them works.

As our Infant/Toddler Coordinator, Ms. McNamara (Ms. Mac), put it, “While we don’t refer to it as a science lesson, infants are introduced to early scientific principles in a number of ways, such as working with water, discovering how magnets work, and food tasting.”

Food tasting activities do more than just broaden a child’s palate and keep all their senses engaged. It’s also an opportunity to show them that even the food they eat has a story to tell. A child who is familiar with pineapple slices at snack time, for instance, will be amazed to see what a whole pineapple looks like and how it grows. Food tasting, then, is a great way to explore new tastes, textures, words, and relationships like parts to whole (as in the pineapple slice being part of the whole pineapple).

Examples

Physical Science: exploring the properties of objects and materials (such as the difference between warm and cold water, a soft and rough surface, spheres and squares, and various colors).

Natural Science: discovering the outdoor world and the living things that are part of it through nature walks and collecting items to observe in the classroom (like rocks, sand, and petals)

Technology

When we hear “technology,” most of us think of smartphones, computers, and complex machines. But technology really encompasses all the tools we create to make our lives easier. For infant and toddlers, that includes scissors, paper, crayons, play dough, and blocks. We show them how they can achieve various small tasks by making use of these and other tools.

Examples

Practical Life Activities: day-to-day practical activities like sweeping, wiping down surfaces, and putting away toys is an important part of the Montessori method. It also shows them how using the right technologies (even if they are very simple, like brooms, cubbies, and wash cloths) can help them achieve their goals.

Engineering

Engineering is all about overcoming challenges by identifying problems, designing solutions, and testing them out.

At its core, engineering is all about cause and effect, and we teach children about this concept through games and activities.

Examples

The In-and-Out Game: placing objects in a closed container and retrieving them helps children understand object permanence (objects that disappear from their sight do not disappear from existence).

Stacking Cups: this activity is a lot of fun, but it’s also self-correcting. Since the cups only fit if they’re in the right order, children will stack them improperly and then fix the order. As Ms. Mac says, “Adults don’t have to tell a child that the cups are not stacked correctly. The stacking cups tell them.”

Art

An art education is a great way to promote the creative and expansive thinking needed to come up with imaginative tasks and solutions.

We provide our students with ample opportunities to practice their artistic skills and express themselves. Out toddler rooms, for example, all have an art easel available for any child who wants to get colorful and channel their inner Van Gogh.

Examples

Process Art: laying out a sheet of paper on the table and letting the students get creative with finger paints, chalk, stickers, crayons, and glue.

Project Art: creating more deliberate art projects, like a dot art rainbow.

Mathematics

So many adults have less than fond memories of learning math. Often, that’s because they were introduced to complex and abstract concepts without first exploring them in a more intuitive way.

Instead of jumping off the deep end, our younger students learn about mathematical concepts through simple, concrete, hands-on activities that involve sorting, matching, recognizing and creating patterns, and differentiating by properties like size.

Examples

Sorting Activities: sorting through things requires comparing and contrasting items based on different criteria, like size or color. Not only is this process the basis of logical thought, it also involves choosing which criteria to sort by, which builds up decision-making skills and personal confidence.

Pink Tower: the Pink Tower is a classic Montessori activity that uses a set of cubes of different sizes. The child arranges the cubes sequentially and then stacks them to build a tower. By seeing the different dimensions and feeling the individual weight of each cube, the child can focus on the unique qualities each of the similar-looking cubes have.

Never Too Soon to Start

STEAM is the cornerstone of a quality education and it is the best preparation to face a rapidly changing and increasingly technological world. So, why put it off? Giving infants and toddlers a foundation in these important subjects is the best way to prepare them for the education they’ll be getting in the coming years.

Infant/Toddler STEAM Series - ECLKC - HHS.gov

Infant/Toddler STEAM Series

View these episodes to explore ways to support STEAM learning for infants and toddlers. STEAM stands for science, technology, engineering, art, and math. In each episode, find an overview of the STEM components and tips for using art to help children explore concepts and skills. Discover strategies and teaching practices to help infants and toddlers develop reasoning, creativity, problem solving, and language and communication skills.

Read more:

STEAM, Scientific Reasoning, Mathematics Development, School Readiness

Infant and Toddler STEAM:

Supporting Interdisciplinary Experiences with Our Youngest Learners

How do science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics (STEAM) relate to infants and toddlers? What can educators do to support the development of infants’ and toddlers’ STEAM-related skills? The authors—a professional development facilitator with experience in early STEAM and an Early Head Start (EHS) teacher who cares for and educates infants and toddlers—along with a cadre of eight other EHS teachers, were curious about finding answers to these questions. This article shares highlights from our journey together as researchers to explore infant and toddler STEAM, make connections between children’s interests and our intentional teaching practices, and create spaces that promote developmentally appropriate STEAM learning.

Teacher Researchers

We approached our study of infant and toddler STEAM as teacher researchers, embracing the idea that early childhood professionals are not only teachers but also learners (Henderson et al. 2012; Edwards & Gandini 2015; Bucher & Hernández 2016). Teacher research emphasizes key inquiry skills such as collaborative dialogue, collection and review of teaching data, and opportunities for reflection on practice (Newman & Woodrow 2015; Marsh & Gonzalez 2018). Through teacher research, teachers can study their professional work, connect theory to practice, and hone their teaching craft through inquiry (Dana 2013; Marsh & Gonzalez 2018).

To do this, nine EHS teachers participated in consistent and continuous professional development that was embedded in their jobs and relevant to their specific contexts and children they served. The teachers—Stephanie (coauthor), Ana Sofía, Sally, Ada, Ellen, Adriana, Rosalind, Mae, and Marie—had a range of experience and qualifications. Four participants held infant/toddler Child Development Associate (CDA) credentials, three held associate degrees in early childhood, and two held bachelor’s degrees in child development or elementary education. All the teachers were female and were between the ages of 35 and 53.

As a group, we met regularly to study early childhood development, observed and documented children’s learning, reflected on their data, and created action plans based on children’s interests. This process helped us to find out more about what STEAM means in the early years, how foundational learning skills relate to STEAM, and what we could do to enhance STEAM in infant and toddler classrooms.

What does STEAM mean in early childhood?

Let us start with what we know about child development. Using the following case studies, which are based on the research group’s many observations from experience as preschool and toddler teachers, take a moment to reflect on how young children from infancy to kindergarten engage with learning:

Curious about what she sees, 9-month-old Emilia scoots toward a flicker of sunlight glimmering from a reflective decoration on the window. She reaches her hand out to try and touch it. She turns her hand around in the flashing light. She clenches her fist a few times and looks up at her teacher, who is observing closely nearby. Emilia furrows her brow as if silently asking about what is happening. Her teacher responds, “It looks like you noticed the light reflecting. Are you trying to catch it, I wonder?”

Two-year-old Alfonso goes immediately to the large cardboard container boxes that his father has placed on the living room carpet for him to explore. Alfonso stacks them as high as he is tall. As he reaches to place another box on top, the stack topples over. Alfonso pauses, and then points and giggles, “Fall down.” His father replies, “Gravity!” Alfonso stacks the blocks again. This time, he swipes his hand against the middle, and down the boxes fall. Alfonso laughs again and says, “It fall down!” His father encourages him to continue building, deconstructing, and testing out his theories.

Marcus and Sherice, both 5 years old, are investigating the natural desert items displayed on a mirror on an outside table.

The teacher has taken time to prepare a variety of natural objects, watercolor paint, permanent markers, and clipboards with paper outdoors as a provocation for children to engage in artistic representation. Sherice chooses to use a magnifying glass to look at the details of a delicate flower more closely before sketching her observations. She uses watercolors to try to capture the hues she sees. Marcus explains to Sherice that he is helping her mix colors to make a shade of red that matches the flower.

What do these case studies have in common? They reveal children’s emerging theories about the world and how they can interact with it. They show children as active, competent, and engaged learners. They also show that learning occurs in the context of relationships with materials and with a nurturing caregiver who is attuned to the child’s strengths and interests.

Infants and toddlers are young scientists conducting research to find out how the world works.

For infants and toddlers, the exploration of STEAM is part of the development of lifelong learning skills in cognitive development and approaches to learning. Early STEAM experiences help develop wonder, persistence, communication, problem solving, and mental flexibility. It is important to note that these skills depend on a child’s developmental abilities and interests and on the extent to which they have a caring, supportive, and secure relationship with their caregiver (Copple & Bredekamp 2009; NAEYC 2019).

When children enter kindergarten, it is very beneficial if they have started to develop foundational learning behaviors such as risk-taking in exploration, close observation, hypothesis formation, analysis based on evidence, and communication. Preschoolers exhibit these skills in a variety of ways. They may use different tools or materials to investigate natural items in their outdoor learning space, identify cause and effect relationships with ramps and pathways in the block center, or represent their ideas through art materials offered in the writing center.

What does STEAM look like in infant and toddler development?

Infants and toddlers are young scientists conducting research to find out how the world works. They are curious to figure things out, like whether they will get the same result when they drop a toy—and have you pick it up—over and over. Infants and toddlers understand concepts, such as cause and effect, that help them build sophisticated reasoning skills and conceptual knowledge (National Research Council 2000; USDHHS 2015; Bucher & Hernández 2016).

Developmental skills

Observable infant and toddler behaviors

Executive function

• persists

• develops confidence

• approaches new experiences and takes risks

• maintains focus and sustains attention

Initiative and curiosity

• shows eagerness and curiosity as a learner

• initiates actions with materials

Creativity

and inventiveness

• experiments with different uses for objects

• is flexible in actions and behavior

Exploration

and discovery

• uses senses to explore

• observes

• makes things happen, watches for results, repeats

• uses understanding of causal relationships

Memory

• recalls and uses information in new situations

Reasoning and problem solving

• uses a variety of strategies, imagination, and creativity to solve problems

• uses spatial awareness to understand properties of objects and their movement in space • applies knowledge to new situations

For example, a 2-year-old might roll a ball down a slide to observe what happens. Then the toddler might retrieve the ball and test it out again. If the ball repeatedly bounces underneath the slide, disappearing from view, the child may exhibit problem-solving skills by changing their movement or rolling the ball up the slide instead, adjusting their approach based on what they see happen. These careful observations and flexibility in thinking show the toddler’s growing understanding of cause and effect and of the properties of materials. When paired with a sense of curiosity to explore and the openness of the teacher to support these types of experiences, infants and toddlers start to figure out how things work and how they can use their bodies to make things happen.

What is unique about caring for infants and toddlers is that their cognitive skills and approaches to learning are made visible through their interactions, not just through their verbal communication. This requires caregivers to closely observe young children to pick up on cues around what interests them and what ideas they may be testing. Infants and toddlers have many expressive nonverbal forms of communication through which caregivers can see their interests, curiosities, approaches, and hypotheses. Children’s observable actions—smiles, hand and body movements, gestures, mimicry, eyebrow furrows, and eye focus—reveal their understandings of the world (Gambetti & Gandini 2014).

Supporting STEAM engagement

with infants and toddlers

We know that learning happens within the context of safe, secure, positive relationships (Copple & Bredekamp 2009; Kovach & Patrick 2012). Through a learning environment that values and actively supports healthy relationships, educators can provide learning provocations that foster STEAM knowledge and skills. The following suggestions from the EHS teachers are offered as complements to build upon nurturing relationships and enriching environments for infants and toddlers.

The chart below shows developmental skills and observable actions related to infants’ and toddlers’ STEAM learning (USDHHS 2015).

Respect children as capable and competent learners.

Young children are capable of observing, interacting, and building hypotheses about the world. “The children were always doing science, we’re just focused on it now,” Ana Sofía explained. By carefully examining their documentation of the children’s actions, the EHS teachers noticed—repeatedly with surprise and awe—that toddlers were intentional, competent, and had their own ideas. “People say they will get bored or have short attention spans,” said Stephanie. “But when you observe closely, children are capable of more than we might think.”

Set up an environment that supports curiosity and engagement.

The teachers saw themselves as STEAM researchers. They engaged in key inquiry components: collaborative dialogue, collection and close examination of evidence related to classroom teaching, and reflection about their teaching practice (Schroeder Yu 2012; Newman & Woodrow 2015; Marsh & Gonzalez 2018). This required the teachers to step back and allow infants and toddlers to explore with minimal intervention. This “intense awareness” was what influenced them to select their instructional strategies, approaches, and provocations (Reggio Children 2016, x).

Observe and document children’s interests and skills. To capture evidence of STEAM skills, teachers can observe and document children’s interactions by taking photos, recording anecdotal notes, and reflecting on their observations (Pelo 2006). Stephanie advised, “It was hard not to do teacher things and interject, but teachers should instead pause to observe children closely. It will help teachers understand what the children are thinking and what they are interested in.” Marie added, “The most organic way of learning is their pure interest.” Ada said, “We’re researching what the children are interested in.” They described their responsibilities as the need to listen, observe, reflect, research, and develop activities based on the data. They used their reflective study of documentation to organize thoughts as a method to look at what children were doing and to meet the children where they were.

Offer interesting materials and experiences that promote problem solving, creativity, and persistence. The teachers intentionally selected materials by reflecting on their observations of children interacting in the classroom. The teachers learned that children were engaged for long periods of time when materials and support from teachers were relevant to their interests. Through their research, the EHS teachers noticed infants and toddlers were interested in observing (looking at and touching fresh flowers, translucent materials, and recycled pieces on a light table), building (stacking with and sitting in boxes), and filling and dumping (putting interesting items inside containers and scooping and pouring sand and water).

Participate in reflective professional development. Quality professional development loops between the teacher’s experiences with children and external sources of content; teachers can observe and interpret evidence of children’s learning through pedagogical reflection in response to children’s, and their own, learning (Scheinfeld, Haigh, & Scheinfeld 2008). In order to better understand how children were developing STEAM knowledge and skills, the EHS teachers reflected on their documentation together. First, the teachers looked for details in the photos and videos. Next, they discussed their observations, which made them more aware of what was happening with children’s development in the classroom.

They asked several questions of their work, such as Is the experience engaging?

How do the children solve problems?

How did the materials or my interactions impact children’s learning?

Then they planned their next steps regarding materials and engagement strategies. Stephanie explained, “For me, reflection was the most important part. It forced me not only to look at how children were learning but also how I was learning to better guide them.” Having developed hypotheses about what the data in their observations meant, the teachers planned to scaffold, reassess, and adjust the environment based on what they learned.

Plan for intentional interactions. Building on children’s interests and evidence of their current abilities and understandings, extend their learning by being intentional. Sally and Ada suggested that educators

Ask open-ended questions like What do you notice?

Why do you think that happened?

What are you thinking about?

Provide new, interesting, developmentally appropriate materials for children to investigate, such as placing mirrors on the floor for an infant’s tummy time or offering a basket of recycled materials to toddlers outside. Teachers may also offer the same materials or variations of a material that infants and toddlers show interest in exploring. For example, teachers can offer smaller boxes to add on to large cardboard boxes that were offered previously.

Model vocabulary and conversations during interactions with children. Teachers might describe the green color of paint a toddler mixed as the hue of steamed broccoli, use phrases like “I think. . .” and “I wonder. . . ”

or narrate their actions during diaper changing (La Paro, Hamre, & Pianta 2007).

It is through these intentional interactions that teachers enhance children’s inquisitiveness, observation of details, and descriptive communication. The table on page 20 offers additional ideas for materials and interactions that support infants’ and toddlers’ STEAM learning.

Conclusion

Even very young children are capable of developing STEAM knowledge and skills. As the EHS teachers gathered and reflected on data to get to know children’s interests and abilities, their practices and interactions became individualized to the unique strengths of the infants and toddlers in their classrooms.

For our youngest learners, STEAM is the development of essential cognitive skills and approaches to learning—like problem-solving, persistence, creativity, and reasoning—that are crucial to early learning and that serve as the foundation for more complex understanding of STEAM content as children grow older. When teachers provide safe and secure relationships, practice intentional observation and documentation strategies, and approach their teaching as learners themselves, they can enhance infant and toddler STEAM.